By. Tara R. Littlefield

Earlier this year, I was working on a project surveying for rare plants and natural communities in the Big South Fork of Kentucky. Hidden in the biologically diverse region of the Cumberland Plateau, we share this region with Tennessee, where headwater streams flow north into Kentucky and create river scour communities along the Big South Fork of the Cumberland River. The Big South Fork is by far one of my favorite places on Earth. The diversity of species, both plants and animals, even undescribed taxon, is astounding. And the river scour communities within this region contain more globally rare plants than anywhere else in Kentucky! This species diversity is only compounded by the complexity of the riparian communities from emergent marshes, outcrops, grasslands, shrublands and woodlands that are maintained by the wild river scour. It’s one of the few places still left in Kentucky where pre-settlement natural conditions still exist, it’s as if you are seeing a landscape that was seen by Native Americans, a true wilderness. And this is also one of our states largest intact forest blocks. It feels ancient, diverse and wise.

Devils Jump , Big South Fork, Kentucky

A tale of Large flowered Barbara’s Button’s

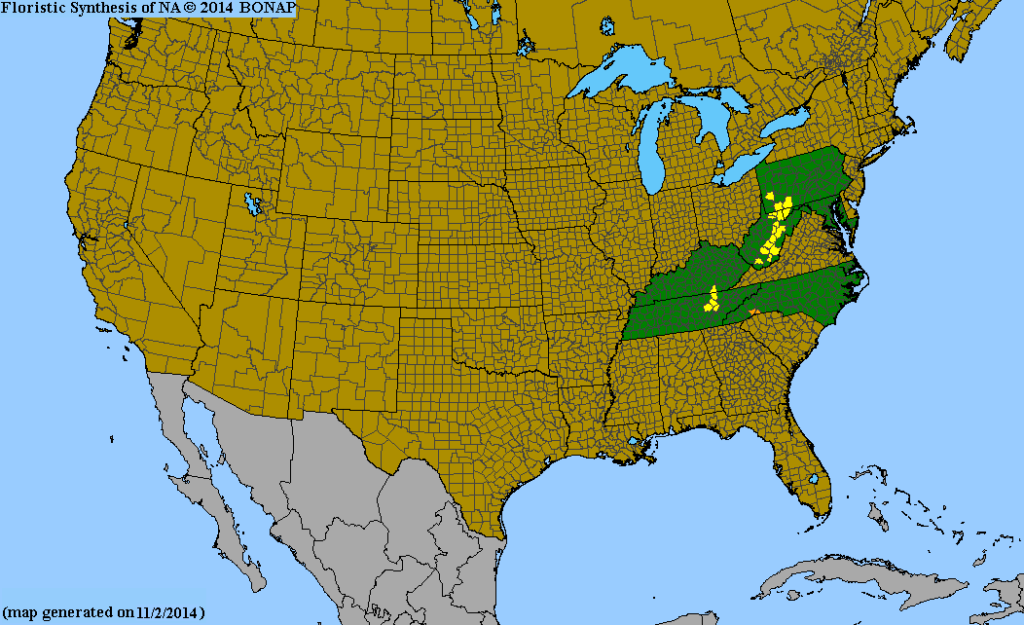

Joining me on the Cumberland Plateau river scour botanical survey team this year were Kentucky Nature Preserves botanists Heidi Braunreiter and Devin Rodgers. This past May 2019, one of our main target species was Barbara’s buttons (Marshallia grandiflora), an elusive rare plant tucked away behind large boulders and cobble on the river scour of the Big South Fork. Marshallia is a genus in the aster family, and all the species within this genus occur in the southeastern United States. Marshalllia grandiflora is endemic to the Appalachians and the Cumberland Plateau, and is currently being assessed for federal listing. It is endangered in Kentucky and Pennsylvania, and threatened in Tennessee and West Virginia, and extinct in North Carolina. The habitat consists of diverse prairioid grasslands that occur on the river scour of several wild rivers. Associated plants of Marshallia consist of species you would find in a prairie such as big blue stem (Andropogon gerardii), Indian grass (Sorgastrum nutans), wild blue indigo (Baptisia australis), blazing stars (Liatris microcephala), sunflowers (Helianthus giganteus, H. hirsutus, H. decapetalus), tall coreopsis (Coreopsis tripteris), st. johns worts (Hypericum sp.), Obedient plant (Physostegia virginiana), goldenrods (Solidago sp.) and asters (Symphytrichum sp.).

Large flowered Barbara’s buttons (Marshallia grandiflora)

small blazing star (Liatris microcephella)

wild blue indigo (Baptisia australis)

wild potato vine (Ipomoea pandurata)

obedient plant (Physostegia virginica)

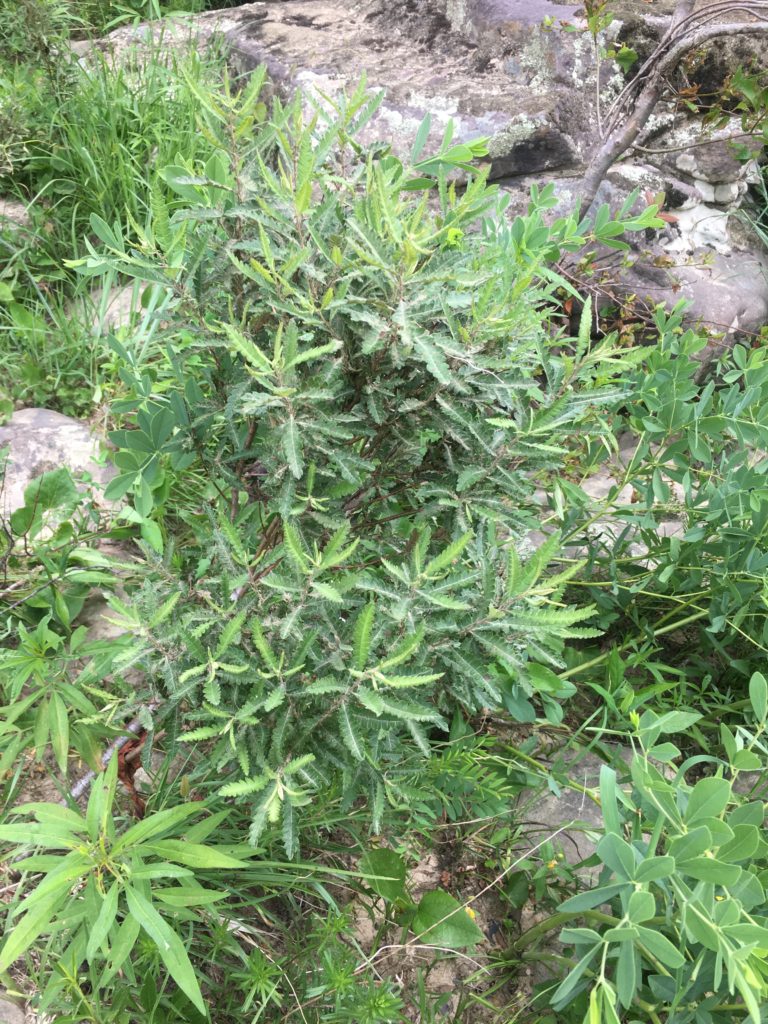

sensitive plant (Mimosa microphylla)

Large flowered Barbara’s buttons are very rare. In Kentucky, at the northern edge of its range in the Cumberland Plateau, this plant is extremely endangered and declining. When we were lucky enough to find a population, only a few single flowers or rosettes had survived. Many questions remain unanswered about this plants life cycle on the Big South Fork of the Cumberland River. How does this perennial stay rooted in the floods? How would seed produced ever have the chance to germinate? I would imagine a deep tap root or an abundance of lateral roots to anchor this plant during the floods, and an ability to live a long life (maybe even thousands of years old), but we just don’t know. And the mammal or bird dispersed seed taking root in the dry months of the summer, quickly sending its taproot to prevent it from being washed away in the next flood. Could a plant’s root break off during a flood, travel downstream and re root in suitable habitat, essentially replanting itself through vegetative reproduction? This is strategy is employed by the Cumberland rosemary (Conradina verticillata), but it is unclear weather Marshallia is able to do this. But a shift in flooding patterns, and changing climate, bring uncertainty and could prevent a seedling from taking hold. There are so many unknowns and confounding factors in the life cycle of this plant.

Life on the river scour can be harsh. Brutal even. For both its inhabitants as well as surveyors like ourselves. There are copperheads and rattlesnakes hiding within these prairies, with massive boulders and logjams slowing our travel. Bouldering and rock hopping is necessary to navigate the jumbled debris. With the rains come floods that roar through the gorge, scouring everything in its path. It’s amazing to me that anything can survive that. But it is this very disturbance that maintains these “prairies of the river,” for without the flooding and scour, shrubs and trees would take hold and the prairie grasses and forbs would disappear. Couple this flooding with summer droughts to keep the trees and shrubs at bay, and the river prairies thrive. Dam these rivers and everything disappears.

Little is known about how long these plants have been hiding out amongst the boulders of the river scour. Likely these disjunct populations from Pennsylvania to Tennessee were connected in the ancient Appalachian landscape. Probably they were more common, and may have evolved within a much more expansive upland ancient prairie habitat that has long ago vanished due to natural large scale climate change, as well as a more connected river scour habitat that is now nearly lost due to damming of rivers and degradation of plant communities from invasive plants, loss and alteration of disturbance regime, and a changing climate. There is even new research into the genetic differences among the extinct North Carolina populations with the rest of the population range, suggesting that there are two different species uniquely evolved in isolation. So what is our role in conserving this unique species? One can only speculate that this species is an ancient plant of a lost world, perhaps evolved in in the ancient upland grassland habitat, but now only found in sheltered ravines codependent on the floods of our protected wild rivers to maintain its habitat and ensure its further existence.

Other interesting rare plants that we encountered on the river scour this year include the globally rare Rockcastle aster (Eurybia saxicastellii), Balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula var. paupercula), Turk’s-cap lily (Lilium superbum), golden club (Orontium aquaticum), the federally threatened Cumberland rosemary (Conradina verticillata) and the boulder bar goldenrod (Solidago racemosa). Included in the mix are intriguing mysteries of possible news species. But there is one rare plant that we encountered on the river scour that has always intrigued me by its glacial relict past, as it seemed to tell the story of these lost worlds with more clarity, of large scale plant migrations over spatial time that us humans can only begin to comprehend, the sweet fern (Comptonia perergina).

Rockcastle Aster (Eurybia saxicastellii)

Turk’s cap lily (Lilium superbum)

Cumberland rosemary (Conradina verticillata)

Balsam ragwort (Packera paupercula var. paupercula)

Sweet Fern-an ancient glacial relict plant lost in the south

The wax myrtle or bayberry family (Myricaceae) is known for its odor. These plants have resinous dots on their leaves, making them aromatic. Plants in this family have a wide distribution, including Africa, Asia, Europe, North America and South America, missing only from Australia. Myricaceae members are mostly shrubs to small trees and often grow in xeric to swampy acidic soils. Familiar members of the wax myrtle family include many in the Genus Myrica (sweet gale, wax myrtle), some of which are used as ornamentals and are economically important. In addition, the wax coating on the fruit of several species of Myrica, has been used traditionally to make candles.

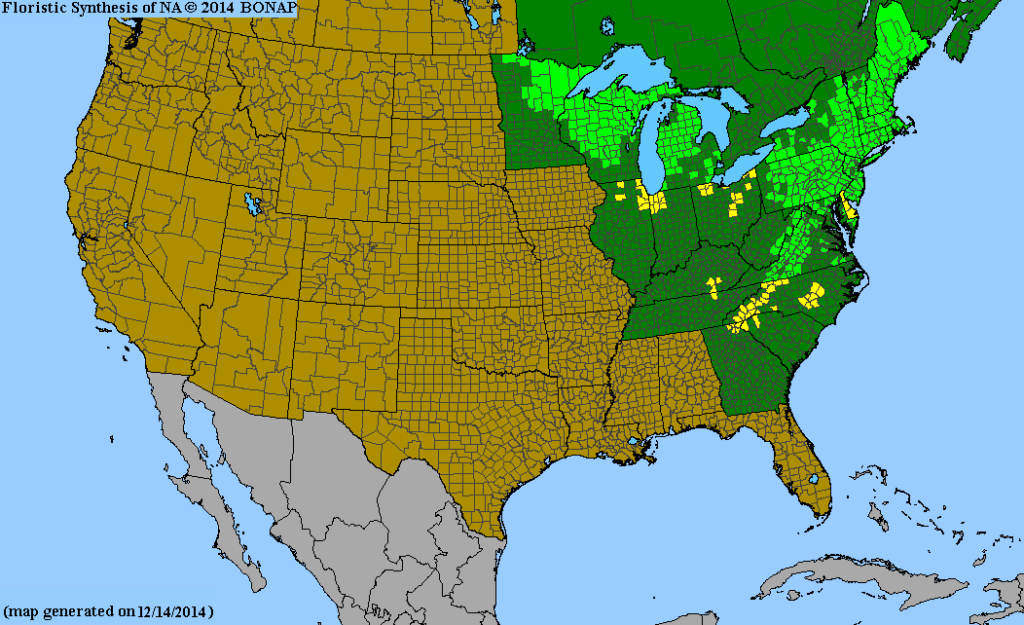

So what place does this interesting family have in Kentucky’s flora? We are lucky to have one species in the wax myrtle family, sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina). In addition, it is also a monotypic genus restricted to eastern North America meaning the genus Comptonia has only one species (C. peregrina) worldwide, and we are lucky it is found here in Kentucky!

The common name sweet fern is misleading. This woody shrub is certainly not a fern. However, the leaves have a similar shape to pinnules of a fern frond. But having sweet in the common name is no mistake. If you crush the leaves, a lovely smell is emitted as the essential oils volatilize into the air.

Sweet fern is a clonal shrub that grows up to one meter high and spreads through rhizomes. The leaves are alternate and simple, linear and coarsely irregularly toothed, dark green above and a bit paler below. It is monoecious meaning male and female flowers occur on different plants. The female flowers are not showy—short rounded catkins that are dense cluster of apetalous flowers, usually associated with oaks, birches and willows with reddish bracts. The male flowers are elongated yellow-green catkins clustered at the branch tips, the pollen being adapted to wind dispersal. The fruit is a round, bur-like cluster of ovoid nutlets that turn brown when mature in late summer. The bark is reddish and highly lenticeled with small corky pores or narrow lines on the bark that allow for gas exchange.

While common in the northern part of its range (northeastern United States and Canada), sweet fern is state listed endangered in Kentucky, along with being state listed as rare in Ohio, Tennessee, South Carolina, West Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina. The populations of sweet fern in the southern part of its range are isolated and disjunct from the common habitats up north. There seems to be a close association of these remnant populations with the Appalachian Mountains, which suggests that the populations in the southern ranges remained in protected “refugia” during periods of great plant migrations that followed glacial cycles.

Sweet fern is typically found in openings in coniferous forests with well drained dry, acidic sandy or gravely soils with periodic disturbances. In the north, it can be found in pine-oak barrens or jack pine and spruce forests that are maintained by fire, creating openings and decreasing competition. It has also been noted to colonize road banks and even highly disturbed soils such as mined areas. Contrary to these open coniferous habitats with periodic fire, the remnant populations of sweet fern in Kentucky and Tennessee are found on sandstone cobble bars, which are maintained by annual floods. Despite being found on habitats that are maintained by different disturbance regimes, these two communities share a few things in common—they are both dry, acidic, sandy and nutrient poor. Disturbances are a natural occurring impact in these communities that removes shrubs and saplings, thus decreasing competition so that sweet fern can thrive.

But perhaps the most fascinating facts about the rare shrub sweet fern is what it can tell us about the evolution of plants, the history of the earth, and the paleovegetational past of Kentucky. Geologically speaking, sweet fern is an ancient plant. In Kentucky, it was likely more common 20,000 years ago during the last glacial period, as Kentucky’s climate was much more like present day Canada. Analysis of pollen in sediment cores taken from natural ponds in Kentucky confirms that spruce and jack pine was common in the uplands in the bluegrass. Sometimes it is difficult to imagine plants migrating north and south in order to adapt to a changing climate. But what is even more mind blowing is that the genus Comptonia is at least 65 million years old. Numerous fossils of dozens of extinct species of Comptonia have been found all across the Northern hemisphere, and the earliest of the fossils have been dated back to the Cretaceous period during the age of the dinosaurs. The first flowering plants evolved only 135 million years ago, making Comptonia is one of the oldest living plants in the world—a true living fossil!

When April 2020 comes around,

and all of the spring wildflowers are emerging, think of sweet fern tucked deep

into the gorges of Big South Fork, its catkins releasing pollen in the wind, think

of Barbara’s buttons withstanding the massive seasonal floods of one of Kentucky’s

last wild rivers. And if you use your

imagination, you may be also be able to see dinosaurs and tree ferns in the

distance. Let us hope sweet fern and Barbara’s buttons

can survive for many millions of years to come.