By Shannon Trimbolli, owner of Busy Bee Nursery and Consulting

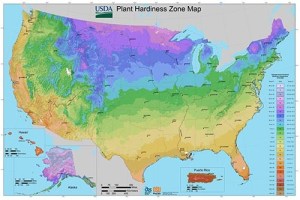

Pick up almost any seed packet, read almost any gardening book, or attend almost any gardening class and you are likely to see a USDA plant hardiness map. The map was developed by the USDA and is based on the average minimum winter temperatures for an area. It divides the country into multiple zones with each zone representing a 10-degree temperature range. Each zone can then be further subdivided. So, for example, where I’m at in Kentucky is zone 6b with an average minimum winter temperature of between 0 and -5 degrees Fahrenheit.

The goal of the plant hardiness zones is to help gardeners determine whether a plant will survive in their gardens. This is especially helpful for exotic ornamental plants, garden veggies, etc. because in garden settings you can presumably control how much water a plant gets, how much fertilizer it gets, etc. However, temperature is the key component that we can’t control and which plays a major role in whether a plant can survive in an area.

The idea of plant hardiness zones and their importance is so ingrained in us that it is common for gardeners to automatically mention what zone they are in when discussing a new plant with other gardeners. This is a good thing because it shows that people are recognizing that the same plant can’t grow in all locations and the person is being conscientious of the growing limitations for where they live. But plant hardiness zones also have their limitations, and one of those limitations is their usefulness for discussions around growing native plants.

Obviously, if a plant is native to a given area, then it can survive that location’s average minimum winter temperature. However, just because a plant can survive an average minimum winter temperature doesn’t mean that it is native everywhere that average minimum winter temperature is found.

For example, parts of New Mexico are in zone 6b, just like I am in Kentucky. However, when I drove through those areas of New Mexico a few years ago, I didn’t see any of my familiar Kentucky native plants naturally growing there. Yes, in controlled garden settings with supplemental watering, people in New Mexico might be able to grow some of the plants that are native to Kentucky, but in that type of situation the Kentucky native plants are being grown as an exotic ornamental plant. They no longer count as a native plant, because they aren’t native to New Mexico.

When it comes to native plants, plant hardiness zones aren’t much use, which makes sense because hardiness zones weren’t developed with native plants in mind. In the world of native plants, ecoregions are what we need to use instead of hardiness zones.

Ecoregions

Ecoregion maps take the entire continent and break it down into areas that have similar temperatures, precipitation, geology, soils, elevations, wildlife, plants, and other characteristics. They do this multiple times at progressively smaller scales to provide both big picture overviews and fine detailed views that can be used as needed for different conservation and resource management goals.

As an example, most of the eastern U.S. falls into the Eastern Temperate Forest Level I Ecoregion. Throughout this region we share many similarities when it comes to our general climate, our native plants, and our native wildlife. However, there are also differences. Despite our similarities, no one would argue that north Florida, the West Virginia mountains, northern Illinois, and most of the rest of the eastern U.S. are exactly the same. That’s where the Level II, III, and IV Ecoregions come into play – each one zooming in closer and looking at things in more detail and at a smaller scale.

As gardeners who are wanting to provide pollinator and wildlife habitat on the local scale, the Level III and IV Ecoregions are the scales that we want to focus on. If you go to the EPA website, they have an interactive map where you can click on your state. Clicking on your state will take you to a page where you can download very detailed maps and posters of the Level IV Ecoregions in your state. They are highly educational, and I encourage everyone to take a look at your state.

Key Differences between Plant Hardiness Zones and Ecoregions

For our purposes, there are two key differences between the plant hardiness zones and the ecoregions. First, ecoregions take into account many more factors than plant hardiness zones. All these different factors make ecoregion maps much more complex. This complexity can be a double-edged sword – it makes the ecoregion maps much richer sources of information, but it also can be potentially overwhelming. The different ecoregion levels can help make the complexity a little less overwhelming because you get to choose how detailed you want or need to get with the information.

Second, plant hardiness zones were developed for gardeners and for use in garden and agricultural settings. Ecoregion maps, on the other hand, were developed for scientists, conservationists, and resource managers focused on ecological issues. That difference in audiences and primary uses can also make ecoregion maps seem a little more complicated, but when planting native plants for pollinators and wildlife, we are creating miniature ecosystems in our yards and communities. That makes us conservationists and resource managers of our backyard and community ecosystems, thus we become part of the audience for which ecoregion maps were developed.

The Importance of Ecoregions for Growing Native Plants

Many plant species are native throughout much of the eastern U.S. / the Eastern Temperate Forest Level I Ecoregion. The sugar maple is one example. However, within its natural range, there is going to be a significant amount of genetic variation that allows a given individual to be better adapted to the specific location in which it is found. If sugar maples from the northern part of their range are planted in the southern part of their range, then those trees will begin to turn colors and lose their leaves earlier in the fall than nearby trees that are from local stock. Other species may have locally adapted genetics that influence the timing of things like the first spring growth, flowering, and leaf emergence.

As gardeners, it may not matter much to us if a plant blooms a little later or produces leaves a little earlier than wild populations in the area. However, some of our bees are pollen specialists which means that they only feed their brood pollen from a certain species, genus, or family of plants. If you plant the right species of flowers, but they don’t bloom when the bees are actively seeking the pollen, then that plant isn’t helping those bees. Butterflies rely on foliage being available for their caterpillars and caterpillars often prefer new growth over older leaves. Birds rely on the caterpillars being available to catch and feed to their babies. And the list goes on. There is a synchronization between the life cycles of many plants and animals that is often not fully recognized or understood.

The genetic variation found within a species range can have impacts purely from a gardening perspective, as well. Some plants, like little bluestem, are known to have tremendous genetic variation within their ranges. In the case of little bluestem, planting seeds from a different ecoregion may result in physical changes such as the plant growing much taller than it would have if it was planted closer to where the seeds were harvested. This can be a problem if you chose little bluestem for your garden because you didn’t want a tall grass in that location. The reason for these physical changes often has to do with things like local genetic adaptations to deal with differences in the soils (sandy, clay, loam) or the amount of moisture in the soils.

Applying Ecoregion Concepts to Your Native Plant Garden

First of all, don’t let the complexity of ecoregions scare you away from planting native plants in your garden. The practical application related to using ecoregional concepts in the garden really isn’t that complicated. Start by just being aware that ecoregions exist and learning a little bit about the ecoregions where you live. However, you don’t necessarily have to memorize what ecoregion you are in.

Personally, I often just say that I’m in southcentral Kentucky instead of saying that I’m in the Interior Plateau Level III Ecoregion or more specifically in the transition zone between the Western Pennyroyal Karst Plain and Eastern Highland Rim Level IV Ecoregions. (And honestly, if you told me what Level IV Ecoregion you were in, I would have to look up its location. I don’t have them all memorized. I’m better with the Level III Ecoregions, but still don’t know all of them.)

However, because I have a general idea of how the Level III and level IV Ecoregions lay out, then by saying that I’m in southcentral Kentucky, I’m still recognizing that central Tennessee is going to be more like where I’m at than far eastern or western Kentucky. I’m keeping that regional perspective, while dropping some of the jargon. It’s that level of knowledge and understanding that I think can be beneficial for native plant gardeners and pollinator enthusiasts.

Next, try to get your seeds from a source as close to you as possible or purchase plants that come from seeds that were sourced as close as possible to you. Most native seed companies and native plant nurseries have no problem having that discussion with you. All you have to do is call or email them. It may surprise them a bit, because most people don’t ask those questions, but they are happy to have those conversations if asked.

The reason I say try to get your seeds from as close as possible to you is because there are only so many native seed companies. There simply may not be a native seed company in your Level III or Level IV Ecoregion. In fact, it is very likely that there isn’t one, especially if you are looking at Level IV Ecoregions. In that case, you do the best you can. For example, if you are in Tennessee, then ordering seed from a native seed company in Kentucky is likely to give you seeds that are more closely adapted to your region than ordering that same species from a native seed company that is multiple states away.

However, that’s not to say that you should never order seeds from companies that are multiple states away. I’ve ordered seeds from companies that were multiple states away because I couldn’t get the species I wanted from a closer source. Like I said, you do the best you can, and “the best you can” may change under different circumstances.

I also don’t want anyone to feel guilty for planting seeds from a different ecoregion or to get analysis paralysis and decide that native plants are too complicated. From a practical standpoint, this whole discussion can be boiled down to some common-sense ways of thinking.

- Native plants don’t care about hardiness zones because their ranges are determined by more than just an average minimum winter temperature.

- Plants that are native throughout a wide range are likely to have genetic variations that make the plants in a given area slightly better adapted to that area than individuals from much further away.

- Getting seeds from a source as close as possible to you gives you the best chance of being able to take advantage of those local adaptations for your area.

- Choose local when possible, but don’t get so hung up on making sure you have sourced your seeds or plants from the exact right ecoregion that you never get around to planting native plants.

- Being native to your area is more important than whether the seeds or plants were sourced from your exact ecoregion.

Reprinted with permission from Backyard Ecology.

Shannon Trimboli enjoys helping people connect with nature in their yards and communities. She owns Busy Bee Nursery and Consulting, which specializes in plants for pollinators and wildlife. She also hosts Backyard Ecology where she provides a free weekly blog and podcast focused on igniting our curiosity and natural wonder, exploring our yards and communities, and improving our local pollinator and wildlife habitat. Learn more at www.backyardecology.net.